Enlightenment and the Scientific Revolution

Units/Unit 4/Enlightenment and Scientific Revolutionary Thought.html

4: The Enlightenment and the Age of Revolution

Enlightenment and the Scientific Revolution

Introduction

The Enlightenment, also known as the Age of Reason, was an intellectual and philosophical movement that dominated the world of ideas during the 18th century. These ideas centered on reason as the primary source of knowledge and advanced ideals such as liberty, progress, toleration, fraternity, constitutional government, and the separation of church and state. The Enlightenment produced numerous books, essays, inventions, scientific discoveries, laws, wars and revolutions. Abolitionists questioned the morality and need for slavery, and eventually succeeded in emancipating enslaved men, women, and children around the Atlantic World. Women challenged the ideas of the state and gained the right to vote after a long Suffrage Movement. This period is one that will set the stage for many events to come in World History, and we can connect many of the events that will occur in future units to the ideas of The Enlightenment.

Save your time - order a paper!

Get your paper written from scratch within the tight deadline. Our service is a reliable solution to all your troubles. Place an order on any task and we will take care of it. You won’t have to worry about the quality and deadlines

Order Paper NowThe central doctrines of the Enlightenment philosophers were individual liberty and religious tolerance, as well as the opposition to an absolute monarchy. The period stimulated people to look at authority in a new way and to posit new and different ideas to remedy the daily problems they encountered. This meant drawing on relatively new ways of interacting with the world. Enlightenment intellectuals argued in favor of empiricism. Empirical thinking posited that knowledge comes from experience or observation rather than belief or tradition. They also championed rationalism. Rationalism was a way of thinking that argued reason was the ultimate test of knowledge and that through rational deduction—breaking the problem down into its constituent parts—they could investigate and understand the logic behind ideas, systems, and experiences. Beyond this, they relied on skepticism, which maintained that nothing was certain until proven. For the Enlightenment intellectuals, proof often came from reason or empirical observation. Finally, cosmopolitanism reflected Enlightenment thinkers’ view of themselves as actively engaged citizens of the world as opposed to provincial and close-minded individuals. In all, Enlightenment thinkers endeavored to be ruled by reason, not prejudice.

The Scientific Revolution

Tracing the beginning of the Enlightenment is difficult, but most agree that it was sparked by the Scientific Revolution, a period of history that lasted from the 16th through the 18th centuries. The Scientific Revolution was an outgrowth of the European Renaissance and Reformation, which we discussed in Unit 2, increased contact with Asia, and the voyages of exploration. The Scientific Revolution took these new ways of thinking—empiricism, rationalism, skepticism, and cosmopolitanism—and asked questions about the natural world. They questioned the authority of classical Roman knowledge and Catholic Church belief by questioning the nature of man and man’s role in the natural world and universe.

Left to Right: Nicholas Copernicus, Galileo Galilei, Johannes Kepler, and Isaac Newton

This was incredibly revolutionary. It opened questions of planetary movement—Nicholas Copernicus (1473-1543) argued with the ideas of the Roman philosopher Ptolemy who argued that the universe’s center was the Earth. Copernicus, after observing the sun’s movement suggested that the sun, and not the Earth, was the center of the universe. A follower of Copernicus’ ideas, Galileo Galilei (1564-1642) conducted experiments to understand the mechanics of items on Earth and in the sky. Galileo’s decision to teach Copernicus’ heliocentric (sun-centered) theory of the universe brought him into conflict with the Catholic Church in Rome and he was ordered to stop teaching it. He did, for a while, but in 1632 he published the Dialogue Concerning Two Chief World Systems, Ptolemaic and Copernican. This brought him back into conflict with the Catholic Church because one of the characters in this dialogue, Simplico, was a fool whose ideas were precisely that of the Catholic Church’s. He was summoned to Rome, tried, and promised never to write. He spent the rest of his life under house arrest.

As Copernicus was beginning to question the center of the universe, Johannes Kepler (1571-1630) opened new lines of inquiry of his own. Kepler posited not only that the universe revolved around the sun and that these movements were mechanical, but that planetary movements were also predictable. He argued that planets move in ellipses, not perfect circles and that there was a way to determine the size of a planet’s orbit from its axis and relationship to the sun. Kepler’s laws of planetary motion form the basis of modern astronomical physics. These intellectuals demonstrate how knowledge built upon itself, it still does, and how intellectuals used each other’s work to go one step further in their analysis. Indeed, Isaac Newton (1642-1726) used Copernicus’ and Kepler’s ideas to help him create an entirely new field of study, calculus. In his Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathmatica (1687) Newton proposed mathematical models for understanding not only the natural world but also the universe.

APPLYING IDEAS TO HUMANS AND PLANTS

It was not only the field of planetary motion that the Scientific Revolution made its mark, but this period also stimulated artists’ and intellectuals’ desires to understand the world around them. When combined with the desires of the Scientific Revolution and its guiding methodologies—empiricism, skepticism, rationalism, and cosmopolitanism—this meant also trying to understand the human body.

During the Renaissance, physicians investigated the human body through direct observation. Andreas Vesalius (1514-1564) observed skeletal, vascular, and muscular systems, creating diagrams and positing explanations with regard to their purposes. As he was uncovering the insides of the body, Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519) investigated the external appearance of the body. Da Vinci was an artist born in the Italian city-state of Florence during the Renaissance and he worked to understand the proportions of the human body and famously created the Vitruvian Man drawing that you see here.

William Harvey (1578-1657), an English scientist, helped launch the field of physiology by investigating the circulatory system. Like Vesalius, he observed the flow of fluids through the body, but unlike Vesalius, he not only traced circulation but proved that bodies have a finite amount of blood that is constantly recirculated. Additionally, he observed and dissected the heart and its chambers, noting how blood moved through the system.

Moving away from the human body, natural philosophers (scientists) began applying what they learned in the human body to plants. Working slightly after Harvey, Robert Hooke (1635-1703) used the microscope to identify the smallest portions of plants, which he named, cells. The idea that plants consisted of small, observable units that could be observed, measured, and compared, was revolutionary.

The observations of natural philosophers (scientists) during the 17th and 18th centuries led to the creation of new and different ways of understanding the world. When combined with the European journeys of exploration and more regular communication between natural philosophers, they needed a way to communicate information without having to constantly restate their experiences. One way they did this was through classification. Aristotle (384-322 BCE) suggested that species existed within a hierarchy with higher life forms on the top and lower on the bottom. During the Scientific Revolution and Enlightenment, these ideas shifted slightly.

Carolus Linneaus (1707-1778), a Swedish botanist and zoologist, published a work entitled the Systema Naturae in which he classified thousands of animal and plant species in a more systemic way than Aristotle’s method. Using the hierarchy—kingdom, phylum, class, order, family, genus, species—Linneaus enabled scientists to group together animals or plants that shared characteristics. When Europeans encountered new animals or plants, there was a way to sort them without disrupting the entire hierarchy—new categories of class, order, family, or genus could be created to accommodate new species. Further, he gave natural philosophers a way to refer to plants and animals—through binomial nomenclature, in which you take the genus and species names and use these to refer to specific animals or plants. This hierarchy based on the shared characteristics of animals or plants enabled natural philosophers to converse with one another about the discoveries they were making and to reach a consensus about the plants or animals being observed through shared scientific naming practices. Without the use of binomial nomenclature, it was possible that scientists observed the same animal, but did not know it.

By the 18th century, this was particularly important as natural philosophers began having the ability to observe plants and, in some cases, animals that never existed prior in Europe. As Europeans traveled abroad some brought new plants and animals back to Europe. The first botanical garden was established in Padua in the mid-16th century and was quickly established elsewhere in the Italian city-states as well as in other European cities, such as Cologne and Prague. In 1621 the University of Oxford established its botanical garden. Botanical gardens became not only a scientific endeavor, but they also helped prove political and economic power. Spain established its Real Jardin Botanico in 1755 and England established the Royal Botanic Gardens in Kew in 1759. It is currently designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Many of the botanical gardens included greenhouses where natural philosophers not only observed their growth and development but also attempted to cultivate them for economic gain.

The Royal Botanic Gardens in Kew

Units/Heading/Tito_Lessi_-_Galileo_and_Viviani.jpg

Units/Unit 4/CopernicusGalileiKeplerNewton.jpg

Units/Unit 4/Vitruvian.jpg

Units/Unit 4/Enlightened Ideas.html

4: The Enlightenment and the Age of Revolution

Enlightened Ideas

Just as the natural philosophers (scientists) of the Scientific Revolution looked to Classical Greece and Rome as a starting point, so too did the Enlightenment intellectuals. Instead of proving the ideas of the classical world incorrect, the Enlightenment philosophers and intellectuals tried to re-create the political systems and moral relationships of the classical era. This was particularly true of the republican and democratic forms of government, which they saw as inherently more fair than the monarchical governments under which many of them lived. In addition to suggesting new forms of government, they also proposed new relationships between the rulers and their subjects. Drawing on the notion of empiricism and skepticism from the Scientific Revolution, these intellectuals proposed new forms of governances and social relations based on the notion of reason. For most Enlightenment intellectuals, reason implied the ability to observe problems and solutions while tracing the changes incrementally through various decisions. Some historians call this the Age of Reason because of their emphasis on this particularly mode of understanding the world.

Just as the natural philosophers (scientists) of the Scientific Revolution looked to Classical Greece and Rome as a starting point, so too did the Enlightenment intellectuals. Instead of proving the ideas of the classical world incorrect, the Enlightenment philosophers and intellectuals tried to re-create the political systems and moral relationships of the classical era. This was particularly true of the republican and democratic forms of government, which they saw as inherently more fair than the monarchical governments under which many of them lived. In addition to suggesting new forms of government, they also proposed new relationships between the rulers and their subjects. Drawing on the notion of empiricism and skepticism from the Scientific Revolution, these intellectuals proposed new forms of governances and social relations based on the notion of reason. For most Enlightenment intellectuals, reason implied the ability to observe problems and solutions while tracing the changes incrementally through various decisions. Some historians call this the Age of Reason because of their emphasis on this particularly mode of understanding the world.

The Enlightenment ideals originated in Western European intellectuals, but eventually spread throughout the world over the course of the next two centuries. In so doing, the ideas first posited by the Enlightenment intellectuals shifted dramatically as new interpretations combined with older expressions of these ideas.

REASON AND THE PERSISTENT QUESTIONS OF RELIGION

Enlightenment intellectuals used reason to question the social and political relationships that, until the Reformation, relied upon the Catholic Church’s sanction. With the Reformation and the wars of religion that followed (1517-1648), many intellectuals eschewed organized religion entirely because it was so bound with political manipulation and war. They argued that instead of looking to organized religion to make an argument, intellectuals should look to nature and derive from nature what they called natural laws. These natural laws were observable (empirical) and could be tested.

While these intellectuals questioned organized religion, they did not generally question the existence of God; indeed many suggested that because He created nature, God exists in nature and the natural laws that intellectuals created were a new way to understand humanity’s relationship to God. Not all intellectuals, however, were so charitable towards religion.

In France, the Catholic Church remained in power after the Reformation, despite significant Protestant populations. The Church and its representatives controlled significant power and wealth within the country, which many Enlightenment intellectuals objected to. Many French intellectuals including Voltaire (1694-1778) and Denis Diderot (1713-1784) questioned the moral basis of the church along lines similar to Martin Luther’s criticisms—they argued the Catholic Church was corrupt. Instead of stopping at this point though, many intellectuals argued that the Catholic Church was corrupt and therefore the entire basis of the Church was also corrupted. They argued that the Catholic Church represented superstition, rather than reason and belief rather than empirical (observable) reality.

L to R: Voltaire, Denis Diderot, David Hume

Voltaire did not stop his criticism there. Unlike many Enlightenment intellectuals, Voltaire did not believe in democracy, but firmly believed in benevolent monarchy. He worried that uneducated individuals and ordinary people would not be able to effectively understand complex political arguments. In the book Candide, Voltaire poked fun at all of Europe. Candide follows a bumbling and optimistic main character from a Germanic kingdom in his travels throughout the world. Through Candide Voltaire questioned the irrationality he saw in European society, particularly with regard to its rigid social rules that divided classes and distributed wealth unequally through these classes. Voltaire criticized the materialism he witnessed in society, not only on the part of laypeople, but also on the part of the Catholic Church. In Candide some of the most corrupt figures are priests. This type of writing forced him to adopt a pen name and to live at least part of his adult life in exile, outside of France.

Denis Diderot read Locke’s work on knowledge and argued a step further. If knowledge was not innate, then belief was not innate either. Diderot used reason to question the power of religion over knowledge and of the Catholic Church and clergy over the people of France. His best-known work is his Encyclopedie. This was a collection of essays and treatises by a number of Enlightenment intellectuals. Diderot used the Encyclopedia to examine what he and others believed were the bases of life—religion, political power, and wealth. Ultimately, many of the books’ contributors argue against mercantilism and, in some cases, against the Catholic Church. They questioned schooling and argued that it failed to teach the key issues of the day—reason, science, and nature.

It was not only the French intellectuals who questioned the role of religion. David Hume (1711-1776), an Englishman, did so too. By employing skepticism, he argued that miracles were not provable. He argued that religion was an intellectual construct created by individuals who needed something to believe in. He argued that no matter how a person understands religion—something revealed through nature or through text, it could not be observed directly and therefore, the phenomenon of religion was not a result of divine revelation, but of human innovation.

These men questioned religion generally because of the way it was practiced during their era and the assumptions that underlined religious theology—supremacy and corruption in church leadership. Whether they were atheists or simply criticized organized religion, they applied the ideas of the Scientific Revolution and Enlightenment to notions of belief in order to understand them.

Units/Unit 4/VoltaireDiderotHume.jpg

Units/Unit 4/Women in the Enlightenment.html

4: The Enlightenment and the Age of Revolution

Women in the Enlightenment

The nature of humanity was not the only way that the Enlightenment challenged the existing ideas of the day. The Enlightenment enabled the questioning of the idea of “man” itself. The role of women in the Enlightenment is frequently overlooked. Women during this era were not considered of equal status to men, and much of their work and effort was suppressed. Salons, coffeehouses, debating societies, academic competitions and print all became avenues for women to socialize, learn and discuss enlightenment ideas. These avenues furthered their roles in society and created stepping stones for future progress.

As the Enlightenment came to advance ideas of liberty, progress, and tolerance, women’s issues were of great importance to the period. For those women who were able to discuss and advance new ideas, discourses on religion, political and social equality, and sexuality became prominent topics in the salons, debating societies, and in print. While women in England and France gained significantly more freedom than their counterparts in other countries, the role of women in the Enlightenment was reserved for those of middle and upper-class families, able to access money to join societies and the education to participate in the debate. Therefore the role of women in the Enlightenment only represented a small class of society and not the entire female sex.

Salons and Coffee houses

Salons were a forum in which elite, well-educated women might continue their learning in a place of civil conversation while governing the political discourse and a place where people of all social orders could interact. In the 18th century, the salon was transformed from a venue of leisure into a place of enlightenment. In the salon, there was no class or education barrier to prevent attendees from participating in open discussion and the salon served as a matrix for Enlightenment ideals as a result. Within the hierarchy of the salons, women assumed the role of governance. Thus, allowing impactful, philosophic discourse to flourish. Consequently, with women at the helm, salons transitioned from an institution of recreation to an active agent within Enlightenment. Suzanne Necker, wife to King Louis XVI of France’s finance minister, is an example of how the salon’s topics are likely to have had a bearing on official government policy. While the elite discussed Enlightenment ideas at various salons, coffeehouse served as venues for middle and working class women to participate in the discourse of the period. People of all levels of knowledge gathered to share and debate information and interests. Coffeehouses where women were involved, like the one run by Moll King, were said to degrade traditional, virtuosic, male-run coffeehouses. King’s fashionable coffeehouse operated into late hours of the night and showed that Enlightenment women were not always simply the timid sex, governors of polite conversation, or protectorates of aspiring artists.

Salons were a forum in which elite, well-educated women might continue their learning in a place of civil conversation while governing the political discourse and a place where people of all social orders could interact. In the 18th century, the salon was transformed from a venue of leisure into a place of enlightenment. In the salon, there was no class or education barrier to prevent attendees from participating in open discussion and the salon served as a matrix for Enlightenment ideals as a result. Within the hierarchy of the salons, women assumed the role of governance. Thus, allowing impactful, philosophic discourse to flourish. Consequently, with women at the helm, salons transitioned from an institution of recreation to an active agent within Enlightenment. Suzanne Necker, wife to King Louis XVI of France’s finance minister, is an example of how the salon’s topics are likely to have had a bearing on official government policy. While the elite discussed Enlightenment ideas at various salons, coffeehouse served as venues for middle and working class women to participate in the discourse of the period. People of all levels of knowledge gathered to share and debate information and interests. Coffeehouses where women were involved, like the one run by Moll King, were said to degrade traditional, virtuosic, male-run coffeehouses. King’s fashionable coffeehouse operated into late hours of the night and showed that Enlightenment women were not always simply the timid sex, governors of polite conversation, or protectorates of aspiring artists.

Significant Women and Publications

Some women, including Olympe de Gouges and Mary Wollstonecraft, used their educations and the opportunities afforded them by the new ideas of the Enlightenment. Women were more involved in publishing their writings than previously thought. In order to publish work during most of the Enlightenment, a married woman had to have written consent from her husband. As the Old Regime began to fail, women became more prolific in their publications. Publishers were no longer concerned about a husband’s consent, and a more commercial attitude was adopted, publishing books that were going to sell. With the new economic outlook of the Enlightenment, female writers were granted more opportunity in the print sphere. As print culture became far more accessible to women in the 18th century, the production of cheap editions and the expanding number of books targeted toward a female readership enabled women to obtain more access to education. Prior to the 18th century, many women gained knowledge from correspondence with males because books were not as accessible to them. Social circles emerged around printed books. While the reading habits of men revolved around silent study, women used reading as a social activity. Reading books in intimate gatherings became a mode that fostered discourse among women. Olympe de Gouges (1748-1793) was a French woman who wrote plays and found her voice alongside many others during the years leading up to the French Revolution. She felt that the ideal of égalité (equality) was unfulfilled, even after the French Revolution began. She penned a scathing rebuke to accompany the “Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen” (DROM). The DROM, a document that set out the ideals of the early French Revolution and the French Republic, sets out the principles of liberty, sovereignty, and freedom. It suggests that “men are born and remain free and equal in rights,” and that there are rights to “liberty, property, security, and resistance to oppression.” It also sets out limits to rights and asserts that “Liberty consists in the freedom to do everything which injures no one else; hence the exercise of the natural rights of each man has no limits except those which assure to the other members of the society the enjoyment of the same rights” and that laws aid in determining how these rights are experienced.

Read: “Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen”

Olympe de Gouges questioned the basis of these rights and re-wrote the DROM in her “The Declaration of the Rights of Woman and the Female Citizen” published in 1791. She inserted the word woman to the original DROM text, suggesting that “woman is born free and lives equal to man in her rights” and “Liberty and justice consist of restoring all that belongs to others; thus, the only limits on the exercise of the natural rights of woman are perpetual male tyranny; these limits are to be reformed by the laws of nature and reason.” Further, she asserted that women should also be subject to laws and must be equally represented by them.

Read: “The Declaration of the Rights of Woman and the Female Citizen”

The rebellion that her words implied was too much for many in the French Enlightenment community to accept, particularly as the revolution moved into its second phase, The Terror. Olympe de Gouges’ ideas and their threat to the overall welfare of society earned her a place in the guillotine during the French Revolution.

Similarly, Mary Wollstonecraft (1759-1797) from England questioned women’s place in society. In 1792, she penned the “Vindication of the Rights of Woman: with Strictures on Political and Moral Subjects.” In this, she questioned a fundamental assumption of English society but stopped short of declaring women equal to men on Earth. Bringing religion into the debate, she argues that morally-speaking men and women are equal, therefore they are equal in the eyes of God. For her, Earth was a different matter entirely. She argued for opportunity—the opportunity for an education similar to men’s, the opportunity to discuss issues on equal footing with men. Although her work was revolutionary, it was largely dismissed within England and in the later 19th century, she became a key figure for suffragettes and those who worked for women’s rights.

Units/Unit 4/Vindication_Wollstonecraft.jpg

Units/Unit 4/Enlightened Despots.html

4: The Enlightenment and the Age of Revolution

Enlightened Despots

Although French monarchs viewed Enlightenment ideals of representation, rule of law, and equality as challenges to their power, other monarchs saw the Enlightenment as an opportunity to reinforce their authority.

The ideals of the Enlightenment stimulated many rulers to re-think the nature of their rule. Indeed, the trend of Enlightened Despotism swept through many courts in Europe. Enlightened Despotism appealed to monarchs because it enabled them to appear benevolent, while maintaining and, at times expanding their absolute authority over their subjects. These monarchs rejected the idea that rights arose from nature or from God, rather within their realms all rights emanated from the monarch individually. They used the idea of granting rights to their subjects as a tool to centralize their own authority.

Frederick the Great of Prussia (1712-1786) and Catherine the Great of Russia (1728-1796) were considered Enlightened Despots.

Frederick the Great of Prussia and Catherine the Great of Russia

Prussia was a Germanic kingdom that under Frederick’s reign became powerful and wealthy. Through war and through his own patronage of the arts, Frederick transformed Prussia from being just one of many Germanic kingdoms into one of the most powerful of the Germanic kingdoms. Militarily, he fought against both Austria and Russia in successive wars to expand territory—the War of Austria Succession (1740-48) and the Seven Years War (1756-1763). In addition to his military success, he reformed Prussian laws and outlawed torture, a subtle nod to the supremacy of law over whim and human rights over oppression.

Catherine the Great

Catherine the Great (1729-1796) was the most renowned and the longest-ruling female leader of Russia, reigning from 1762 until her death in 1796. She was born in Prussia and came to power following a coup d’état when her husband and grandson of Peter the Great, Peter III, was assassinated. The period of Catherine the Great’s rule, the Catherinian Era, is often considered the Golden Age of the Russian Empire. During her reign, Russia was the world’s largest land empire, built on an economic basis of territory, agriculture, logging, fishing, and furs.

Catherine the Great

An admirer of Peter the Great, Catherine continued to modernize Russia along Western European lines. Thanks to Catherine, Russia grew larger and stronger than ever and became recognized as one of the great powers of Europe. She governed at a time when the Russian Empire was expanding rapidly by conquest and diplomacy. In the south, she defeated the Ottomans and colonised vast territories along the coasts of the Black and Azov Seas. In the west, she gained a portion of Poland and began to colonize Alaska (a territory that will be purchased by the United States in 1867).

Catherine continued to modernize Russia along Western European lines. She enthusiastically supported the ideals of the Enlightenment, and is often regarded as an enlightened despot. As a patron of the arts she presided over the age of the Russian Enlightenment, a period when the Smolny Institute, the first state-financed higher education institution for women in Europe, was established. Under Catherine, the Russian state also created a system of laws and a law code that she hoped would reinforce her absolute authority, support the state’s continued prosperity, and limit the power of the nobles. For instance, in her Proposals for a New Law Code she argued that “the Equality of the Citizens consists in this; that they should all be subject to the same laws.” By suggesting that somehow all her subjects were equal and below her, she bolstered her own status while reminding her nobles that they were her subjects. In addition to reforming the laws, Catherine also corresponded regularly with other intellectuals, patronized the arts, and imagined herself an intellectual in her own right.

However, military conscription and the Russian economy continued to depend on serfdom, a system that increased due to the increasing demands of the state and private landowners. Both Catherine and Frederick II were absolutists, meaning they believed their power was without equal in their realms. However, their dedication to creating laws and changing social norms demonstrates their interpretation and institution of Enlightenment ideals. Nonetheless, they remained ruthless autocrats that worked to increase their country’s power and wealth, largely for their own benefit.

Units/Unit 4/FrederickCatherine.jpg

Units/Unit 4/The Enlightenment and Georgia.html

4: The Enlightenment and the Age of Revolution

The Enlightenment and Georgia

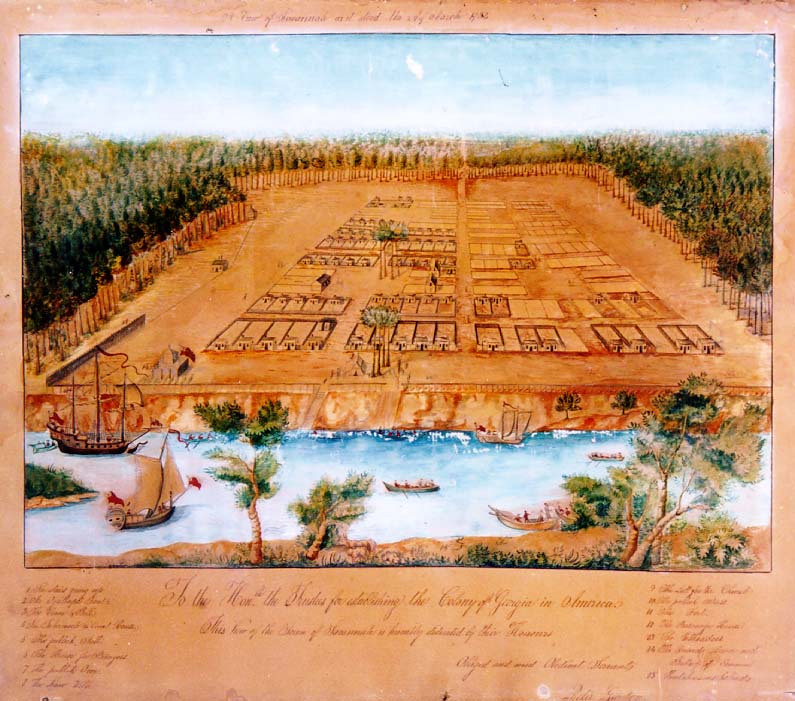

The reach of Enlightenment thought was both broad and deep, and it even has connections to Georgia History! In the 1730s, having witnessed the terrible conditions of debtors’ prison, as well as the results of releasing penniless debtors onto the streets of London, James Oglethorpe—a member of Parliament and advocate of social reform—petitioned King George II for a charter to start a new colony. George II, understanding the strategic advantage of a British colony standing as a buffer between South Carolina and Spanish Florida, granted the charter to Oglethorpe and 20 like-minded proprietors in 1732.

Oglethorpe led the settlement of the colony, which was called Georgia in honor of the king. In 1733, he and 113 immigrants arrived on the ship Anne. Over the next decade, Parliament funded the migration of 2500 settlers, making Georgia the only government-funded colonial project.

The Oglethorpe Plan was an embodiment of all of the major themes of the Enlightenment, including science, humanism, and secular government. Georgia became the only American colony infused at its creation with Enlightenment ideals: the last of the Thirteen Colonies, it would become the first to embody the principles later embraced by the Founders. Remnants of the Oglethorpe Plan exist today in Savannah, showcasing a town plan that retains the vibrancy of ideas behind its conception.

At the heart of Oglethorpe’s comprehensive and multi-faceted plan there was a vision of social equity and civic virtue. The mechanisms supporting that vision, including yeoman governance, equitable land allocation, stable land tenure, and secular administration, were among the ideas debated during the British Enlightenment. Many of those ideals have been carried forward, and are found today in Savannah’s Tricentennial Plan and other policy documents.

Oglethorpe’s vision for Georgia followed the ideals of the Age of Reason. He saw Georgia as a place for England’s “worthy poor” to start anew. To encourage industry, he gave each male immigrant 50 acres of land, tools, and a year’s worth of supplies. In Savannah, the Oglethorpe Plan provided for a utopia: “an agrarian model of sustenance while sustaining egalitarian values holding all men as equal.” Oglethorpe’s vision called for alcohol and slavery to be banned. However, colonists who relocated from other colonies—especially South Carolina—disregarded these prohibitions. Despite its proprietors’ early vision of a colony guided by Enlightenment ideals and free of slavery, by the 1750s, Georgia was producing quantities of rice grown and harvested by enslaved people.

Table of Contents.html

| Surv World History/Civiliz II Section 04G Summer 2019 CO – The Enlightenment1. The Enlightenment and the Scientific Revolution

2. Enlightened Ideas 3. Women in the Enlightenment 4. Enlightened Despots 5. The Enlightenment and Georgia |